The history

of the Republic of India began

on 26 January 1950. The country became an independent nation within the British Commonwealth on 15 August 1947. Concurrently the

Muslim-majority northwest and east of British

India was separated into the Dominion of Pakistan, by the partition of India. The partition led

to a population transfer of more than 10 million people between

India and Pakistan and the death of about one million people. Nationalist

leader Jawaharlal Nehru became the first Prime Minister of

India and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel became the Deputy Prime Minister of India and its Minister of Home Affairs. But the most

powerful moral leader Mahatma

Gandhi accepted no office. The

new constitution of 1950 made India a secular and a democratic state. It has a Hindu

majority, a large Muslim minority, and numerous other religious minorities

including Sikhs and Christians.

The nation faced religious violence, casteism, naxalism, terrorism and regional separatist insurgencies,

especially in Jammu and Kashmir and northeastern India. India has

unresolved territorial disputes with China, which, in 1962, escalated into the Sino-Indian

War, and with Pakistan, which resulted in wars in 1947, 1965, 1971 and 1999. India was neutral in the Cold War, but purchased its military

weapons from the Soviet Union, while its arch-foe Pakistan was closely tied to

the United States.

India is a

nuclear-weapon state; having conducted its first nuclear test in 1974 followed by another five tests in 1998. From the 1950s to the 1980s, India

followed socialist-inspired

policies. The economy was shackled by regulation,

protectionism and public

ownership, leading to pervasive corruption and slow economic growth.[ Beginning in 1991, significant economic reforms have transformed India into the third largest and one

of the fastest-growing economies in

the world. Today, India is a major

world power with a prominent voice in global affairs and is seeking a permanent seat in the United Nations Security Council. Many

economists, military analysts and think tanks expect India to become a superpower in the near future.

Home to the ancient Indus Valley Civilisation and a region of

historic trade routes and vast empires, the Indian subcontinent was identified

with its commercial and cultural wealth for much of its long history. Four

world religions—Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism, and Sikhism—originated here,

whereas Zoroastrianism, Christianity, and Islam arrived in the 1st millennium

CE and also helped shape the region's diverse culture. Gradually annexed by and

brought under the administration of the British East India Company from the

early 18th century and administered directly by the United Kingdom from the

mid-19th century, India became an independent nation in 1947 after a struggle

for independence that was marked by non-violent resistance led by Mahatma

Gandhi.

The Indian economy is the

world's tenth-largest by nominal GDP and third-largest by purchasing power

parity (PPP). Followingmarket-based economic reforms in 1991, India became one

of the fastest-growing major economies; it is considered a newly industrialised

country. However, it continues to face the challenges of poverty, illiteracy,

corruption, malnutrition, inadequate public healthcare, and terrorism. A

nuclear weapons state and a regional power, it has the third-largest standing

army in the world and ranksseventh in military expenditure among nations. India

is a federal constitutional republic governed under a parliamentary

systemconsisting of 28 states and 7 union territories. India is a pluralistic,

multilingual, and multiethnic society. It is also home to a diversity of

wildlife in a variety of protected habitats.

India , officially the

Republic of India , is a country in South Asia. It is the

seventh-largestcountry by area, the second-most populous country with over 1.2

billion people, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the

Indian Ocean on the south, the Arabian Sea on the south-west, and the Bay of

Bengal on the south-east, it shares land borders with Pakistan to the west;

China, Nepal, and Bhutan to the north-east; and Burma and Bangladesh to the

east. In the Indian Ocean, India is in the vicinity of Sri Lanka and the

Maldives; in addition, India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands share a maritime

border with Thailand and Indonesia.

The name India is derived

from Indus, which originates from the Old Persian word Hindu. The latter term

stems from the Sanskrit wordSindhu, which was the historical local appellation

for the Indus River. The ancient Greeks referred to the Indians as Indoi ,

which translates as "the people of the Indus". The geographical term

Bharat (pronounced [bharat] , which is recognised by the Constitution of India

as an official name for the country, is used by many Indian languages in its

variations. The eponym of Bharat is Bharata, a mythological figure that Hindu

scriptures describe as a legendary emperor of ancient India. Hindustan was originally a Persian word that meant

"Land of the Hindus"; prior to 1947, it referred to a region that

encompassed northern India and Pakistan. It is occasionally used to solely

denote India in its entirety.

Etymology

The name India is derived from Indus, which originates from the Old Persian word Hinduš. The latter term stems from the Sanskrit word Sindhu, which was the historical local appellation for the Indus River. The ancient Greeks referred to the Indians as Indoi (Ινδοί), which translates as "the people of the Indus". The geographical term Bharat(pronounced), which is recognised by the Constitution of India as an official name for the country, is used by many Indian languages in its variations. The eponym of Bharat is Bharata, a theological figure that Hindu scriptures describe as a legendary emperor of ancient India. Hindustan was originally a Persian word that meant "Land of the Hindus"; prior to 1947, it referred to a region that encompassed northern India and Pakistan. It is occasionally used to solely denote India in its entirety.

History

Ancient India

Anatomically modern humans are thought to have arrived in South Asia 73-55,000 years back, though the earliest authenticated human remains date to only about 30,000 years ago. Nearly contemporaneous Mesolithic rock art sites have been found in many parts of the Indian subcontinent, including at the Bhimbetka rock shelters in Madhya Pradesh. Around 7000 BCE, the first known Neolithic settlements appeared on the subcontinent in Mehrgarh and other sites in western Pakistan. These gradually developed into the Indus Valley Civilisation, the first urban culture in South Asia; it flourished during 2500–1900 BCE in Pakistan and western India. Centred around cities such as Mohenjo-daro, Harappa, Dholavira, and Kalibangan, and relying on varied forms of subsistence, the civilisation engaged robustly in crafts production and wide-ranging trade.

During the period 2000–500 BCE, in terms of culture, many regions of the subcontinent transitioned from the Chalcolithic to the Iron Age. The Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed during this period, and historians have analysed these to posit a Vedic culture in the Punjab region and the upper Gangetic Plain. Most historians also consider this period to have encompassed several waves of Indo-Aryan migration into the subcontinent from the north-west. The caste system, which created a hierarchy of priests, warriors, and free peasants, but which excluded indigenous peoples by labelling their occupations impure, arose during this period. On the Deccan Plateau, archaeological evidence from this period suggests the existence of a chiefdom stage of political organisation. In southern India, a progression to sedentary life is indicated by the large number of megalithic monuments dating from this period, as well as by nearby traces of agriculture, irrigation tanks, and craft traditions.

In the late Vedic period, around the 5th century BCE, the small chiefdoms of the Ganges Plain and the north-western regions had consolidated into 16 major oligarchies and monarchies that were known as the mahajanapadas. The emerging urbanisation and the orthodoxies of this age also created heterodox religious movements, two of which became independent religions. Buddhism, based on the teachings of Gautama Buddha attracted followers from all social classes excepting the middle class; chronicling the life of the Buddha was central to the beginnings of recorded history in India. Jainism came into prominence during the life of its exemplar, Mahavira. In an age of increasing urban wealth, both religions held up renunciation as an ideal, and both established long-lasting monastic traditions. Politically, by the 3rd century BCE, the kingdom of Magadha had annexed or reduced other states to emerge as the Mauryan Empire. The empire was once thought to have controlled most of the subcontinent excepting the far south, but its core regions are now thought to have been separated by large autonomous areas. The Mauryan kings are known as much for their empire-building and determined management of public life as for Ashoka's renunciation of militarism and far-flung advocacy of the Buddhist dhamma.

The Sangam literature of the Tamil language reveals that, between 200 BCE and 200 CE, the southern peninsula was being ruled by the Cheras, the Cholas, and the Pandyas, dynasties that traded extensively with the Roman Empire and with West and South-East Asia. In North India, Hinduism asserted patriarchal control within the family, leading to increased subordination of women. By the 4th and 5th centuries, the Gupta Empire had created in the greater Ganges Plain a complex system of administration and taxation that became a model for later Indian kingdoms. Under the Guptas, a renewed Hinduism based on devotion rather than the management of ritual began to assert itself. The renewal was reflected in a flowering of sculpture and architecture, which found patrons among an urban elite. Classical Sanskrit literature flowered as well, and Indian science, astronomy, medicine, and mathematics made significant advances.

Medieval India

inThanjavur was completed

in 1010 CE by Raja Raja Chola I.

The Indian early medieval age, 600 CE to 1200 CE, is defined by regional kingdoms and cultural diversity. When Harsha of Kannauj, who ruled much of the Indo-Gangetic Plain from 606 to 647 CE, attempted to expand southwards, he was defeated by the Chalukya ruler of the Deccan. When his successor attempted to expand eastwards, he was defeated by the Pala king of Bengal. When the Chalukyas attempted to expand southwards, they were defeated by the Pallavas from farther south, who in turn were opposed by the Pandyas and the Cholas from still farther south. No ruler of this period was able to create an empire and consistently control lands much beyond his core region. During this time, pastoral peoples whose land had been cleared to make way for the growing agricultural economy were accommodated within caste society, as were new non-traditional ruling classes.The caste system consequently began to show regional differences.

In the 6th and 7th centuries, the first devotional hymns were created in the Tamil language. They were imitated all over India and led to both the resurgence of Hinduism and the development of all modern languages of the subcontinent. Indian royalty, big and small, and the temples they patronised, drew citizens in great numbers to the capital cities, which became economic hubs as well.Temple towns of various sizes began to appear everywhere as India underwent another urbanisation. By the 8th and 9th centuries, the effects were felt in South-East Asia, as South Indian culture and political systems were exported to lands that became part of modern day Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, Philippines, Malaysia, and Java. Indian merchants, scholars, and sometimes armies were involved in this transmission; South-East Asians took the initiative as well, with many sojourning in Indian seminaries and translating Buddhist and Hindu texts into their languages.

After the 10th century, Muslim Central Asian nomadic clans, using swift-horse cavalry and raising vast armies united by ethnicity and religion, repeatedly overran South Asia's north-western plains, leading eventually to the establishment of the Islamic Delhi Sultanate in 1206. The sultanate was to control much of North India, and to make many forays into South India. Although at first disruptive for the Indian elites, the sultanate largely left its vast non-Muslim subject population to its own laws and customs. By repeatedly repulsing Mongol raiders in the 13th century, the sultanate saved India from the devastation visited on West and Central Asia, setting the scene for centuries of migration of fleeing soldiers, learned men, mystics, traders, artists, and artisans from that region into the subcontinent, thereby creating a syncretic Indo-Islamic culture in the north. The sultanate's raiding and weakening of the regional kingdoms of South India paved the way for the indigenous Vijayanagara Empire. Embracing a strong Shaivite tradition and building upon the military technology of the sultanate, the empire came to control much of peninsular India, and was to influence South Indian society for long afterwards.

Early modern India

Writing the will and testament of

the Mughal king court in Persian, 1590–1595

In the early 16th century, northern India, being then under mainly Muslim rulers, fell again to the superior mobility and firepower of a new generation of Central Asian warriors. The resulting Mughal Empire did not stamp out the local societies it came to rule, but rather balanced and pacified them through new administrative practices and diverse and inclusive ruling elites, leading to more systematic, centralised, and uniform rule. Eschewing tribal bonds and Islamic identity, especially under Akbar, the Mughals united their far-flung realms through loyalty, expressed through a Persianised culture, to an emperor who had near-divine status.The Mughal state's economic policies, deriving most revenues from agriculture and mandating that taxes be paid in the well-regulated silver currency, caused peasants and artisans to enter larger markets. The relative peace maintained by the empire during much of the 17th century was a factor in India's economic expansion, resulting in greater patronage of painting, literary forms, textiles, and architecture. Newly coherent social groups in northern and western India, such as the Marathas, the Rajputs, and the Sikhs, gained military and governing ambitions during Mughal rule, which, through collaboration or adversity, gave them both recognition and military experience. Expanding commerce during Mughal rule gave rise to new Indian commercial and political elites along the coasts of southern and eastern India. As the empire disintegrated, many among these elites were able to seek and control their own affairs.

By the early 18th century, with the lines between commercial and political dominance being increasingly blurred, a number of European trading companies, including the English East India Company, had established coastal outposts. The East India Company's control of the seas, greater resources, and more advanced military training and technology led it to increasingly flex its military muscle and caused it to become attractive to a portion of the Indian elite; both these factors were crucial in allowing the Company to gain control over the Bengal region by 1765 and sideline the other European companies. Its further access to the riches of Bengal and the subsequent increased strength and size of its army enabled it to annex or subdue most of India by the 1820s. India was then no longer exporting manufactured goods as it long had, but was instead supplying the British empire with raw materials, and many historians consider this to be the onset of India's colonial period. By this time, with its economic power severely curtailed by the British parliament and itself effectively made an arm of British administration, the Company began to more consciously enter non-economic arenas such as education, social reform, and culture.

Modern India

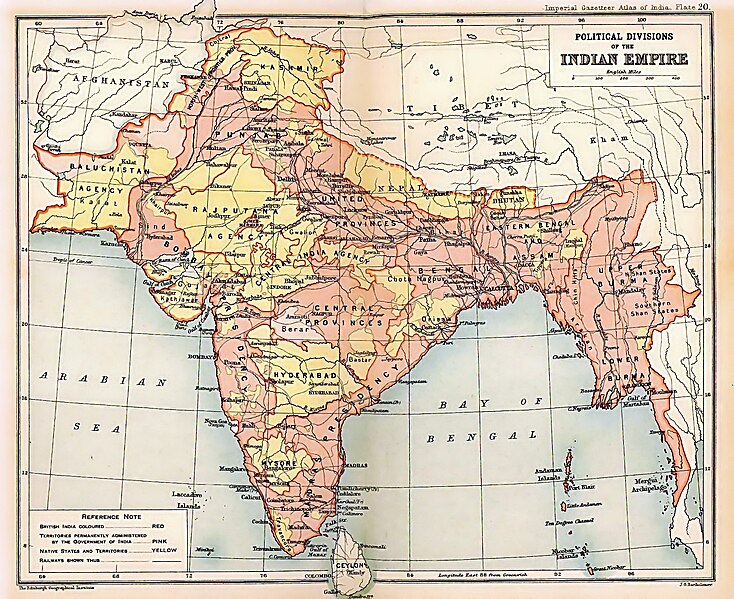

The British Indian Empire, from the 1909 edition of The Imperial Gazetteer of India. Areas directly governed by the British are shaded pink; the princely states under British suzerainty are in yellow.

Jawaharlal Nehru (left) became India's first prime minister in 1947.

Mahatma Gandhi (right) led the independence movement.

The rush of technology and the commercialisation of agriculture in the second half of the 19th century was marked by economic setbacks—many small farmers became dependent on the whims of far-away markets. There was an increase in the number of large-scale famines, and, despite the risks of infrastructure development borne by Indian taxpayers, little industrial employment was generated for Indians. There were also salutary effects: commercial cropping, especially in the newly canalled Punjab, led to increased food production for internal consumption. The railway network provided critical famine relief, notably reduced the cost of moving goods, and helped nascent Indian-owned industry. After World War I, in which some one million Indians served, a new period began. It was marked by British reforms but also repressive legislation, by more strident Indian calls for self-rule, and by the beginnings of a non-violent movement of non-cooperation, of which Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi would become the leader and enduring symbol. During the 1930s, slow legislative reform was enacted by the British; the Indian National Congress won victories in the resulting elections. The next decade was beset with crises: Indian participation in World War II, the Congress's final push for non-cooperation, and an upsurge of Muslim nationalism. All were capped by the advent of independence in 1947, but tempered by the partition of India into two states: India and Pakistan.

Vital to India's self-image as an independent nation was its constitution, completed in 1950, which put in place a secular and democratic republic. In the 60 years since, India has had a mixed record of successes and failures. It has remained a democracy with civil liberties, an activist Supreme Court, and a largely independent press. Economic liberalisation, which was begun in the 1990s, has created a large urban middle class, transformed India into one of the world's fastest-growing economies, and increased its geopolitical clout. Indian movies, music, and spiritual teachings play an increasing role in global culture. Yet, India has also been weighed down by seemingly unyielding poverty, both rural and urban; by religious and caste-related violence; by Maoist-inspired Naxalite insurgencies; and by separatism in Jammu and Kashmir and in Northeast India. It has unresolved territorial disputes with China, and with Pakistan. The India–Pakistan nuclear rivalry came to a head in 1998. India's sustained democratic freedoms are unique among the world's new nations; however, in spite of its recent economic successes, freedom from want for its disadvantaged population remains a goal yet to be achieved.

No comments:

Post a Comment